Weekend Special: The Modern Graphic Novel

A reading list if you want to learn more about the world of graphic novels.

This Sunday, we dive into the world of graphic novels. This is not a list of graphic novels you should read but rather a collection of articles and essays about them. If you are, however, looking for such a list, there are a few I can recommend: This list by The Guardian is an excellent and diverse start. The Top 10 list of Time in 2006 is still relevant. If you are looking for a more expansive list, this list of 50 graphic novels from CBR can keep you busy for months.

But what is a graphic novel anyway? Aren't they all just comics? There is no clear definition here, and many authors are against using the term. One of the most prominent writers of the medium, Alan Moore (who we will talk about more), thinks it's just a marketing term. Other authors have chimed in with similar views, but one of my favorite comments on the topic is from Jeff Smith, author of the Bone series, in this interview:

I just recently read Douglas Wolk say, when people ask him what the difference is between a graphic novel and a comic book, he says, "the binding." Which, I kind of like that answer. Because "graphic novel"... I don't like that name. It's trying too hard. It is a comic book. But there is a difference. And the difference is, a graphic novel is a novel in the sense that there is a beginning, a middle and an end. I don't consider a collected story arc of Spider-Man a graphic novel. It's not. There may be superhero stories that are.

We also have to define some geographic boundaries. As we examine them in this list, graphic novels refer to American and British publications. There is a whole other world to be explored when it comes to comics from continental Europe and Japan. If you would like to do that, maybe this article exploring the rising popularity of comic books in France can be a good starting point.

For our list, we will primarily look at three different eras of the graphic novel. This is by no means an official distinction or even a widely endorsed one, but when I think about my journey reading graphic novels, most of the stuff I've read falls within one of these three: The birth of the modern GN, the Vertigo era, and the Image era.

The birth of the graphic novel is not easy to trace. Will Eisner's A Contract With God is widely considered the first graphic novel. That is not entirely true, but it is not altogether wrong either. In truth, it's fairly complicated. With that, our first recommended article is from Vulture: Will Eisner and the Secret History of the Graphic Novel. Eisner wanted "Contract" to be treated as serious literary fiction and went to great lengths to ensure its high production values and mainstream distribution. The book's success helped elevate comics as an art form and inspired a new generation of graphic novelists.

If you picked up one of the 1,500 copies of the first edition of A Contract with God offered through comic book shops, you would be holding a volume that outwardly appeared to be much like every traditional hardcover on your shelf: No illustration marred the type on its cover; there was no dust jacket; and no copy indicated that it was a graphic novel, comic, cartoon, or anything other than the serious literature that Eisner dreamed it could be treated as. But inside you were immediately pulled into Eisner’s world, with endpapers of the dingy alleys of the Bronx, the skyscrapers of Manhattan faintly looming in the distance, and a defeated man making his way up a staircase.

Despite being such a pioneering work, Contract does not get as much recognition as other books that have contributed to recognizing graphic novels as a serious art form. That honor probably goes to Art Spiegelman's Maus, the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer prize. The first volume was published in 1986, and the second in 1991. I will leave you with a few readings on this book. First, these lecture notes by Ian Johnston are an excellent study of not only Maus but also art in general.

But there are moments when Spiegelman challenges this easy identification with Vladek and calls into question his own artistic style—forcing us to break our contact with the narrative and reflect upon just what's going on here. What sort of a book is this? What is the relationship between the enjoyment I am deriving from my reading and what the book is trying to say?

This New York Times review of the second volume also delves into the delicate balance between memory and storytelling. Finally, the article Past and Present from The Nation explores how Maus remains a powerful and influential work while reviewing Maus Now, a collection of essays on Maus.

Most people don't think of Contract and Maus when they hear "comics." Where are the superheroes? You could even argue that the term "graphic novel" itself was coined to distinguish more serious works from them. This was also a time of uncertainty for the comic book industry. Towards the end of the 1970s, DC, one of the larger publishers, had imploded, and the quality of Marvel publications was dropping. This article from The Artifice provides a very easy-to-digest version of their decade-by-decade history. What concerns us most is that new publishers entered the scene at the beginning of the 1980s, with creator-owned comics rising in popularity. That will bring us to one of the most important years in graphic novel history: 1986.

In my opinion, the most important GN published in 1986 (it wasn't collected as a full volume until 1987) was Watchmen. The name comes from the Latin phrase "Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?", and it changed comic books forever. We could compile an entire reading list on Watchmen alone, but let's start with a good introductory article from The Guardian: Watchmen: The moment comic books grew up.

In an essay in Harvard Divinity Bulletin by Jonathan Schofer, Ethics and Vulnerability in Watchmen highlights the flawed nature of the costumed vigilantes, who struggle with moral ambiguity, violence, and a lack of clear ethical guidepost.

Nothing in Watchmen undermines subtle philosophical theories of ethics, but through these characters we repeatedly see ethical ideals invoked to justify and often sincerely motivate deeply problematic action. Watchmen explores many other limits to the ethical life, in body and psyche. The heroes age, gain weight, and lose their strength. Some express doubts and regrets.

In his Substack, Dan Liebke discusses a more overlooked aspect of Watchmen, a pilot twist where the villain Ozymandias reveals he has already carried out his master plan, subverting the typical superhero trope of the villain monologuing about their scheme. Alan Moore's America: The Liberal Individual and American Identities in Watchmen is a more academic look at the title topic and is well worth a read:

In the figure of Ozymandias, Alan Moore iterates the primacy of the individual, but in the interest of the collective. He is the self-made man and capitalist philanthropist rolled into one.

Finally, before we move on from Watchmen, I want to mention HBO's excellent recent TV adaptation via the article by The Atlantic titled Watchmen Is a Blistering Modern Allegory.

The other highly influential GN published in 1986 is Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns. If you read it today, you might think that it is just another Batman story, but that's because it shaped that idea for the decades to come. Its influence is also a bit different from Watchmen's in the sense that, beyond the story itself, it was revolutionary in how to tell a good story in this medium. I highly recommend reading The Dark Knight Returns: Art Makes Sense If You Force It To by H. W. Thurston to understand more. Thurston argues how the book's use of color, visual pacing, and intertextual references elevate it as an exemplary work of comic art.

But lots of mediums can have poetic and narrative rhythm. What excited me the most about The Dark Knight Returns was its visual rhythm. I had no preconceptions about what one could do with two-dimensional space in that way. So I was fascinated when the book turned out to be full of visual punchlines and callbacks. Its sense of visual rise and fall, and its ability to weave multiple threads together on any given page, is basically symphonic.

1986 was an important year outside of these graphic novels. Peter Sanderson's writings on the topic are worth a read if you want to explore more. Start with Part 1 and Part 2, but the series keeps going if you want to dive deeper.

Moving on from 1986, we proceed into the second era we will cover in this post: Vertigo, an imprint of DC that focuses on creator-owned comics. We can start with How Vertigo Changed Comics Forever, which was published in Vulture. It serves as a great introduction to what Vertigo was and what it did and a good primer on what creator-owned comics are.

You knew that the Vertigo label meant there was something interesting about what was underneath the cover. It was the best of both worlds: the financial ethics of an indie company with the selling (and hiring) power of a multinational corporation.

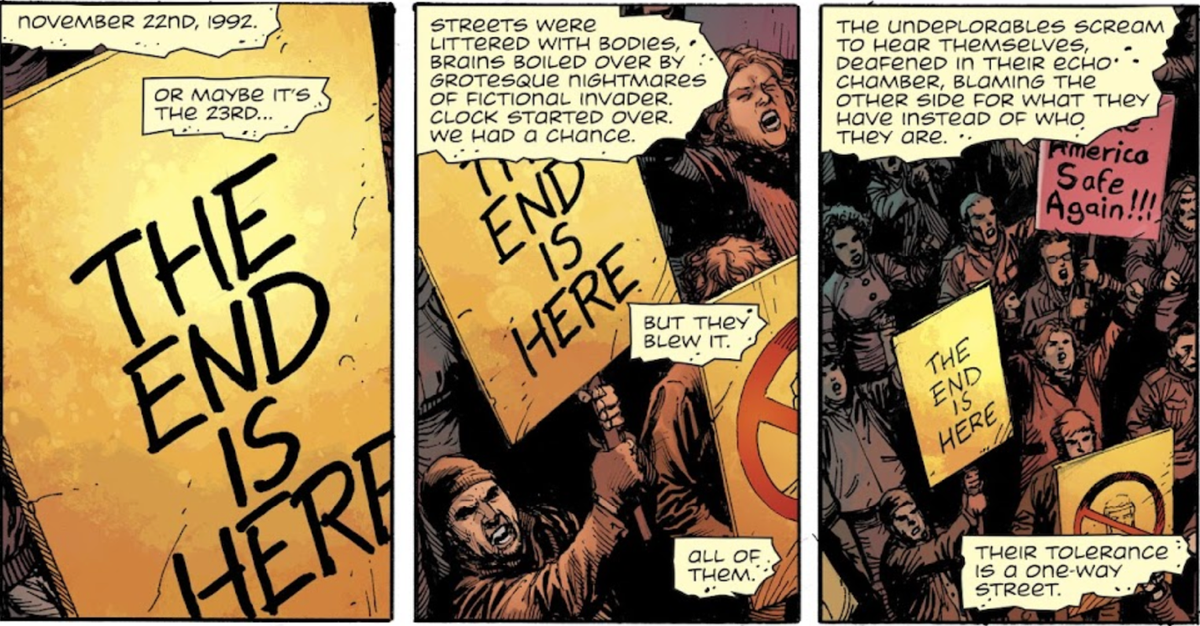

If you would like to read another overview, another article in a similar tone is Vertigo: How the DC Imprint Changed Comics Forever. It's hard to pick individual publications from their line-up to focus on, but one of my favorite GNs from the Vertigo era is Transmetropolitan. In some ways, it's more relevant today than it was first published, as this article from the Guardian suggests: Transmetropolitan: the 90s comic that's bang up-to-date on Donald Trump.

Another long-lived series was Bill Willingham's Fables, which ran for 162 issues, not counting the spinoffs. Paste Magazine published a good introduction to it as it was nearing the end of its run. This more academic writing, "We All Live in Fabletown: Bill Willingham’s Fables—A Fairy-Tale Epic for the 21st Century," explores how this series reimagines classic fairy tale characters, subverting traditional narratives and exploring their personal autonomy. It also celebrates the characters' capacity for change and the primacy of community over dogmatic ideologies. Willingham was also part of a more recent controversy around Fables. After disagreements with DC, he announced that he was releasing it to the public domain. DC, of course, disagreed.

Throughout its lifetime, Vertigo published so many graphic novels that would be very influential in popular culture. One you will recognize from TV is Preacher. In How a Western Comic Series Made Me the Texan I Am Today in Texas Monthly, the author recounts how the comic book series shaped his identity and perception of Texas after his family moved there from Indiana as a teenager.

It was the sort of nuance that I craved as I was building my own identity: I was old enough to know that the tropes of many of the stories Preacher invoked were jingoistic, sexist, and racist—but also that they were fun, exciting, and cool, and I was thrilled to find a comic book that was as interested as I was in trying to reconcile those things.

Hellblazer ran for 300 issues and was adapted to a movie and a TV show. Sandman by Neil Gaiman was very influential, even before it was adapted to what I thought was a mediocre TV show. This interview with Gaiman in The Guardian has a lot of information about the history of graphic novels and their inspirations.

A successful writer can enjoy a whole career without creating a classic. Gaiman created his right out of the gate. To those who read it, The Sandman was as much a part of the 90s as Twin Peaks and Nirvana.

It feels bad to skip over other great titles by Vertigo: 100 Bullets, Sweet Tooth (also a TV show), The Invisibles, American Vampire, The Unwritten, Animal Man, The Books of Magic... the list goes on. However, we must move on to Vertigo's spiritual successor: Image, which brings us to the third era we will cover.

Thanks to the excellent The House of ‘The Walking Dead’ published in The Ringer, I don't need to bother with an introduction. It explores the company's founding, the challenges it faced, and how it became one of the most influential and successful independent comic book publishers. You'll discover that the key to Image's longevity and success was its innovative creator-owned model.

In 1991, when a comics creator left Marvel, they’d head to DC for work, or vice versa. McFarlane didn’t want that to be the expectation, so after the Marvel meeting, McFarlane and Lee went to DC’s offices. While McFarlane had worked for DC in the past, Lee hadn’t. Because of that, “they thought they hit the mother lode,” McFarlane said. . . . “We get into the meeting and we go, ‘By the way, we’re here to tell you the same thing. We’re not here to work for you, either,’” McFarlane said. “When we walked out of DC, that was day one of Image being official.”

The most recognizable publication coming out of Image is most likely The Walking Dead. With an adapted TV show that was also massively popular, its success is undebatable. Check out this interview with the creator, Robert Kirkman, for insights on both the TV show and the comics.

As you dive deeper into Image's catalog, you will find many other incredibly creative graphic novels. One that I find very interesting is Chew. It's an offbeat comic series about a cop with psychic powers from what he eats. The Creator-Owned Ideal: Looking at the Story Behind Chew provides a great read on this series. It explores how Chew has been praised as an example of the creative freedom and success possible with creator-owned comics and is seen as an influential work that inspired other creators to pursue their unconventional ideas.

I said it earlier and I’ll say it again – Chew is a weird as hell book – but for it to work, it needed a pair of creators who would be willing to commit to the idea in a way most would be fearful of.

Image's biggest hit since The Walking Dead came with Saga, co-created by Fiona Staples and the industry veteran Brian K. Vaughan. This article from The Atlantic explores how at its core, the series is a sprawling, genre-blending tale about the power of family and the resilience of the human spirit. Another piece from WWAC argues that the series' appeal lies in its powerful message of diversity, freedom, and the right to choose one's own path in life, regardless of societal norms or expectations.

Here’s the point: to all of us readers, Saga gives a promise of freedom to be whoever we want and make our own choices without fear of being judged or punished. “Diversity is beautiful!” every page screams, as the book gets us acquainted with a Noah’s Ark of fiction species.

If you want something more quirky, you could try East of West by Jonathan Hickman. This review on thefandomentals.com praises it, especially for its world-building.

As we wrap things up, I want to close with an article from Vice: The Image Union Is the Future of Comics. Amidst all the fandom, it can be easy to forget that comics and graphic novels are an industry, and much like other creative industries, its heavily powered by workers. This article is about the Comic Book Workers United (CBWU) union, which was formed by Image employees who felt overworked and underpaid, especially during the pandemic. They also want a process for dealing with creators accused of misconduct.

While this has been a long list, we could barely scratch the surface. There are a plethora of other publishers and important works that are not from Vertigo or Image, and arguably, they are even more interesting and diverse. Maybe we will get a chance to cover them in another weekend special.