Richard Linklater & His Movies

For this weekend special, we dive into Linklater's movies, and the writing around them.

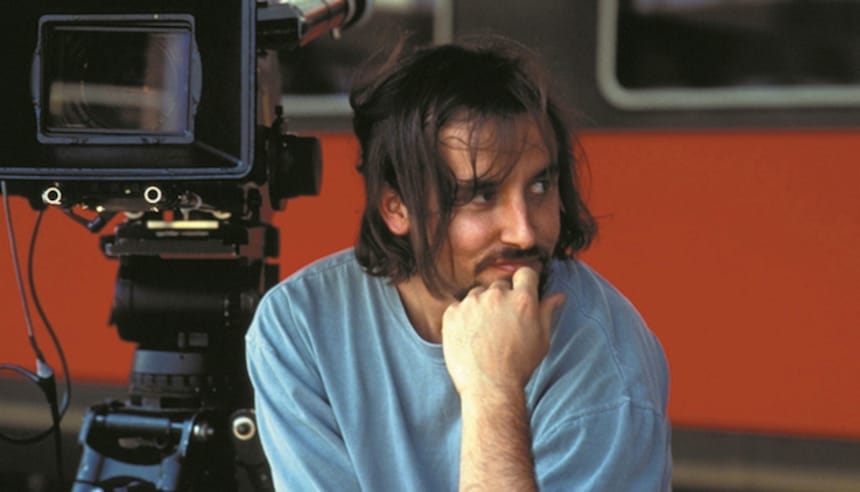

For this weekend's special, we will take a look at Richard Linklater, his films, and, of course, the writing around them for our reading list. I heard very few people mention his name when asked for a favorite director, but I also haven't met anyone who didn't like his work.

Linklater's films span multiple genres, but his style has a few hallmarks: naturalistic dialogue, time as a theme, a slice-of-life approach, and how location usually plays an important part. Another essential part of his identity is that he is a Texan, and my pick to introduce him as a director comes from his home state, Texas Monthly.

Linklater is often seen as the laid-back filmmaker of Austin, but his journey reveals a relentless drive and passion for cinema that shaped the Texas film scene. This piece, “Richard Linklater, the Everyday Auteur,” dives into Linklater's early days, his unique approach to filmmaking, and his commitment to elevating other voices in the industry. We also learn how his early experiences in Houston and Austin shaped his unique storytelling style, focusing on the beauty of everyday life and chance encounters.

Linklater’s most critically lauded movies tend to be . . . films that focus on his fascination with the unpredictable ways that chance encounters with others can shape our lives.

Linklater's first feature film was Slacker, a low-budget production set in Austin, presenting a series of loosely connected vignettes featuring an eclectic cast of characters. It has been highly influential in defining that culture, but it also serves almost as a documentary snapshot of Austin going through gentrification. This piece from The End of Austin titled “The Slacker Colonialist and the Gentrification of Austin” explores the complex story of gentrification in Austin. The author uses the figure of the "Slacker" from the movie to examine the cultural shifts and the uncomfortable realities of displacement that have accompanied the city's growth.

In an interview several years after Slacker was released, Linklater said that he did not realize at the time that the movie was “documenting the end of something.” He said he only came to realize later that he was recording the last days of a subculture in Austin, a subculture that was transformed by the 1990’s technology boom and the erosion of Austin’s low-cost lifestyle, especially the availability of cheap rent.

Another article from Texas Monthly is in the same spirit. “Thirty Years After ‘Slacker,’ the Film Is an Austin Time Capsule—And a Hopeful Tribute to Its Spirit” reflects on the film's lasting impact and the bittersweet nostalgia it evokes for the film and the city of Austin.

Slacker presents the city as a universe willed into existence by those who chose not to do anything. It’s a liminal way station floating between the places where you’re supposed to be, which means you can just do whatever you want.

Linklater’s next film, Dazed and Confused, is now considered a cult classic. This essay, written for the Criterion Collection, “Dazed and Confused: Dream On” captures its essence perfectly and celebrates the film as a genuine portrayal of a unique moment in time.

Linklater has always been devoted to the little things, the tiny details that gradually accumulate and make up the big picture. He has never been one to start off with a bang. With this supposedly unassuming opener, he had found the perfect link between sound and image.

Also, if you are interested in reading more about Dazed and Confused, check out this book, “Alright, Alright, Alright” by Melissa Maerz, an oral history of the movie. The article “How Richard Linklater Created a Legend with ‘Dazed and Confused’” from Rolling Stone also introduces this book, and it is a good read on its own.

Gen X went to see the movie, then sat in the parking lot outside the theater arguing over it, then got on our land-lines the next morning to tell our friends they had to see it. It became a word-of-mouth phenomenon. Yet somehow the mystique keeps growing, as an evergreen lets-watch-it-again classic.

Many movie lovers, including myself, learned about Linklater through Before Sunrise. I don’t think anyone knew then that it would become a trilogy. The movies are not only set in nine-year intervals but were also filmed nine years apart. Through them, we follow a couple's relationship over almost three decades.

A lot has been written about this trilogy, and it’s hard to pick only a couple among them. One thing I find interesting is how the last movie has more of a supporting cast, while for Sunrise and Sunset, the location itself, Vienna and Paris, respectively, play that role. With that, one piece I quite enjoyed reading is "Traveling Scene to Scene in the Streets of Vienna, Before Sunrise” by Stephen Kelman. He reflects on a personal journey through Vienna, retracing the steps of Jesse and Celine from the film. It’s a thoughtful look at how fiction can shape our experiences and perceptions of love.

And so, the sun dipping over the rooftops, its light draining from the sky so that our dusk resembled their dawn, we felt the presence of Jesse and Celine and of the twist of fate that would part them. In grasping the imaginative cord that joined us we were also communing with the version of us that didn’t make it, because time had ran out for us as it had for them.

Another good piece of writing on the trilogy is from Criterion again: “The Before Trilogy: Time Regained.” Dennis Lim explores how their conversations reflect not just the passage of time but also our struggles with love and mortality. His writing is an excellent study of all three films.

Each film is a window onto a stage of life, sharply attuned to the possibilities and disappointments of one’s twenties, thirties, and forties. Taken together, they have become something much larger and more radical: an ongoing collective experiment in embodying the passage of time.

A Scanner Darkly by Philip K Dick is one of my favorite novels, and back in the day, I was incredibly excited to learn that Linklater would adapt it. It’s not the kind of book that you would expect to get adapted to the big screen. Definitely not with a big cast with Keanu Reeves (at the height of his Matrix fame), Robert Downey Jr., Woody Harrelson, and Winona Ryder. On top of that, it was going to be a rotoscoped animation. If Linklater had not pulled off Waking Life a few years earlier, I don’t think this movie would ever get made. In hindsight, it’s hard not to look at Waking Life and think how it would be the perfect way to adapt A Scanner Darkly.

My recommended reading on this movie is Brian Eggert’s essay, “A Scanner Darkly.” It delves into how the film mirrors Dick's insights into reality and perception, inviting us to reconsider our judgments about addiction and the cultural forces that are behind it. This piece offers a fascinating look at a film that remains relevant and unsettling decades after its release.

All these devices—scanners, drugs, animation—are filtering devices within the film. They distance the viewer or the subject from the truth, for which knowledge thereof is impossible, thus brilliantly placing us on the same disjointed plane of existence as the protagonist.

Two of Linklater’s movies, Bernie and Hit Man, are based on Texas Monthly articles covering real crimes in Texas. Both are incredibly good reads. “Midnight in the Garden of East Texas” by Skip Hollandsworth was published back in 1998 and is the basis for the movie Bernie. In this intriguing piece, we unravel the bizarre tale of Bernie Tiede, a man adored by his East Texas community, who admitted to killing a wealthy widow, Marjorie Nugent. As the story unfolds, it examines the strange dynamics of their relationship and the townspeople's surprising support for Bernie, making it a captivating exploration of morality, perception, and the complexities of small-town life.

At the grocery store and at Daddy Sam’s, other women came up to the district attorney and said they were praying for him to do the right thing. A disgusted Danny Buck told me, “It’s almost as if everyone has already forgotten that an elderly lady was shot to death.”

I was surprised to learn that the other article, “Hit Man,” which Linklater adapted with the same name, was also written by Skip Hollandsworth. This story is about the life of Gary Johnson, a former police officer turned informant who poses as a hitman to catch would-be murderers. Full of chilling anecdotes and unsettling encounters, the article reveals the bizarre psychology of those seeking lethal solutions to their problems and Johnson's weird role in this dark underworld.

What Johnson knows, perhaps better than anyone else, is the capability of people, given certain circumstances, to do absolutely savage things to each another. It’s a good bet that someone in that restaurant with us that day was probably wishing someone else was dead.

The last released movie I want to mention before wrapping up is Boyhood. Its relationship with time is very similar to the Before trilogy, except it was shot continuously over 12 years and released as a single movie. It chronicles a boy's growing up with divorced parents. My first recommended read is from Senses of Cinema, “Richard Linklater’s Boyhood and the problem of aging in film” by Rick Zinman. It’s an in-depth look into cinematic portrayals of aging, characters' struggles as they navigate the complexities of growing up, the search for father figures, and ultimately, mortality.

By not replacing his child actors, Linklater shows the audience that it is possible to preserve a child’s identity on film when she or he grows up. It is as if Linklater wants to assure us, contrary to everything we have previously seen on film, that we can indeed hold on to our childhood memories and experiences when we grow up.

The other article I want to highlight comes from a The Guardian interview, “Richard Linklater and Ellar Coltrane: 'Making Boyhood was a dear process’” by Kate Kellaway. In this conversation, Linklater and Coltrane reflect on this unique filmmaking journey and the emotional complexities of portraying a childhood that intertwines with the realities of life, family, and the passage of time. Their candid discussion offers a glimpse into the film's profound impact on both their lives.

One feels there is a family likeness here that extends beyond their laid-back aura to their thinking. It becomes obvious before even the first five minutes have passed that these men are talkers; they spark off each other – meeting them is the closest one can come to stepping into a conversation in a Linklater film.

Finally, I want to wrap things up with an excellent profile by Nathan Heller in the New Yorker published right after Boyhood was released, “Moment To Moment.” It serves almost as a summary of everything we’ve read so far, exploring how Linklater's experiences and vision shape his movies and inviting us to reflect on the nature of time and growth in cinema.

Going against the fashions of contemporary filmmaking, Linklater’s notion of cinematic refinement has less to do with virtuosic camerawork than with creating a moment that’s worth capturing.